Cheating at Chess

DrLupo, Marina Keegan, and a Twitch charity tournament gone awry

I have played chess most of my life, but I really got back into it over the pandemic. I bought courses, watched professionals streaming on Twitch, analyzed my matches to see where I went wrong, and generally tried to get better. My interest in the ancient game waxes and wanes, though recently I’ve even been having fun beta-testing Duolingo’s chess course thanks to a friend who works there.

When you mention you play chess, people like to ask “how good are you?” That’s a difficult question if you don’t know how good the person asking is. What I normally say is “I’m good compared to people who don’t take chess seriously, and I’m bad compared to people who do.”

Chess does have a rating system—Elo—that allows you to be more precise about this, but it’s only useful if you are familiar with the system and know what to benchmark it against. Right now on Chess.com I’m 1803 at the Rapid Format (99.1 percentile for the site), 1602 at Blitz (96.5 percentile) and 1541 at Bullet (96.5 percentile). Given that Chess.com players are already a self-selecting bunch, that’s not bad, especially since I have only a couple of openings in my repertoire.

Then again, I was hosting a work event recently where someone casually mentioned they played chess, and I suggested that maybe we could play. Turns out they’re a 2300. I’d have a better chance of beating him than getting elected Pope, but just barely.

I have never cheated at chess. But I have been tempted. Every chess player, I imagine, has been tempted at one point or another. It is easy to cheat—all you have to do is ask a chess engine on a separate device what you should do in your position. If you do this enough times, because computers are better than humans at chess, you will win. When you win you feel smart and accomplished and victorious. Your Elo score goes up, and that feels good too. If you aren’t careful, you can even start thinking that the Elo score is a proxy for your intelligence and so having it go up is a signal that you’re that much smarter and better than everyone else.

Of course, the reason you don’t cheat is that none of this is true. The win will feel hollow and fraudulent, because it is and you are. In real life no one cares about your Elo score, and even if they do, it certainly is not a good proxy for your intelligence. My dad once considered hiring a grandmaster chess player (fewer than two thousand in world!) for a software job on the basis that if he was that good at chess, he’d be amazing at anything. Unfortunately, he couldn’t pass even the most basic coding test the position required.

There is a Machiavellian reason not to cheat too: you are likely to get caught. The detection algorithms are really quite good, and you will be ashamed when people find out you are a cheater.

But mostly, you shouldn’t cheat because what’s the point? You are presumably playing chess to learn and have fun. Cheating won’t help you do either. For professionals the calculus is a little different—you might win more money and sponsorships if you cheat, but if you get caught you will be shunned and lose out on your career. For most of us, however, if you can take one step outside of your amygdala, cheating at chess doesn’t make any sense.

Enter DrLupo, a streamer playing in the Twitch chess tournament PogChamps 6.

PogChamps is a tournament where gamers or online personalities who are not professional chess players compete for charity. Beforehand the players get paired with professional chess players and tutors to help them be presentable. The fun part about the tournament is precisely that these are amateurs playing one another. Their mistakes and flops are silly and entertaining. It’s easier to follow along even if you aren’t an advanced player. It’s for charity. I watched the first few PogChamps tournaments during the pandemic and had fun.

I do not know DrLupo, he is not one of the people I followed when I was actively watching Twitch. He’s apparently a 38-year-old streamer with over 2 million followers, known for his charity streams for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and playing battle royale games.

His rating on Chess.com in Rapid was 600, while his opponent on PogChamps was 1350, more than double—and the improvement curve is not linear. I mentioned my ratings before so you could get a sense that this is a massive gap. It is a difference in countless hours of study and practice. The 1350 has likely put serious time into chess, the 600 has likely not.

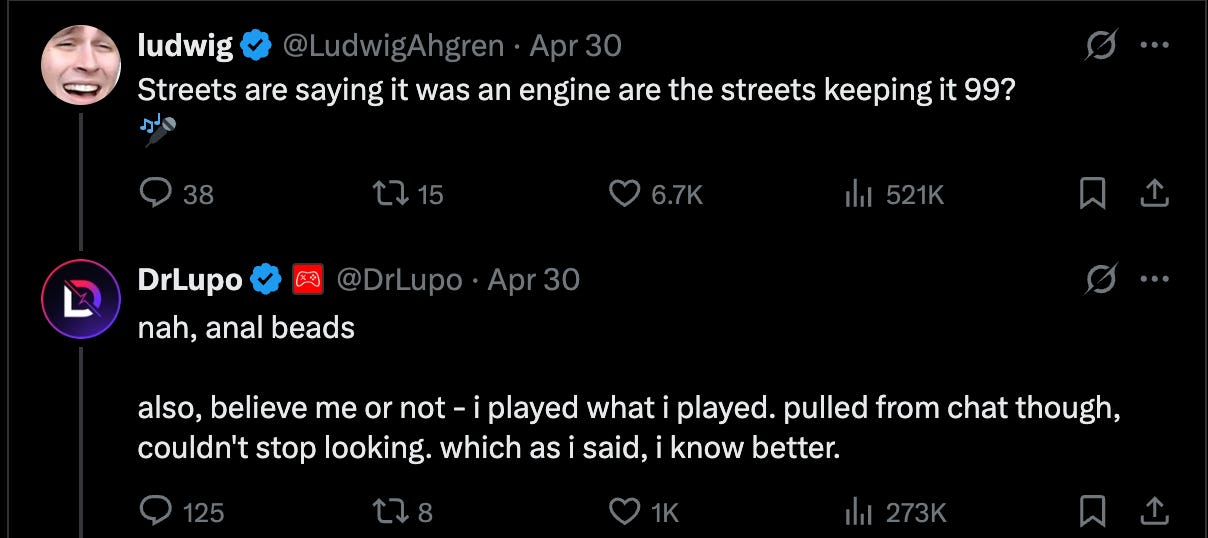

DrLupo denied he outright cheated. In his first statement, he said he looked at the chat function of Twitch. This would still be considered cheating at a professional chess tournament, but is an understandable “mistake.”

Of course, DrLupo cheated the normal way—by checking an engine. Everyone watching could tell—the signs are obvious—and Chess.com, after analyzing the game, closed his account for fair play violations.

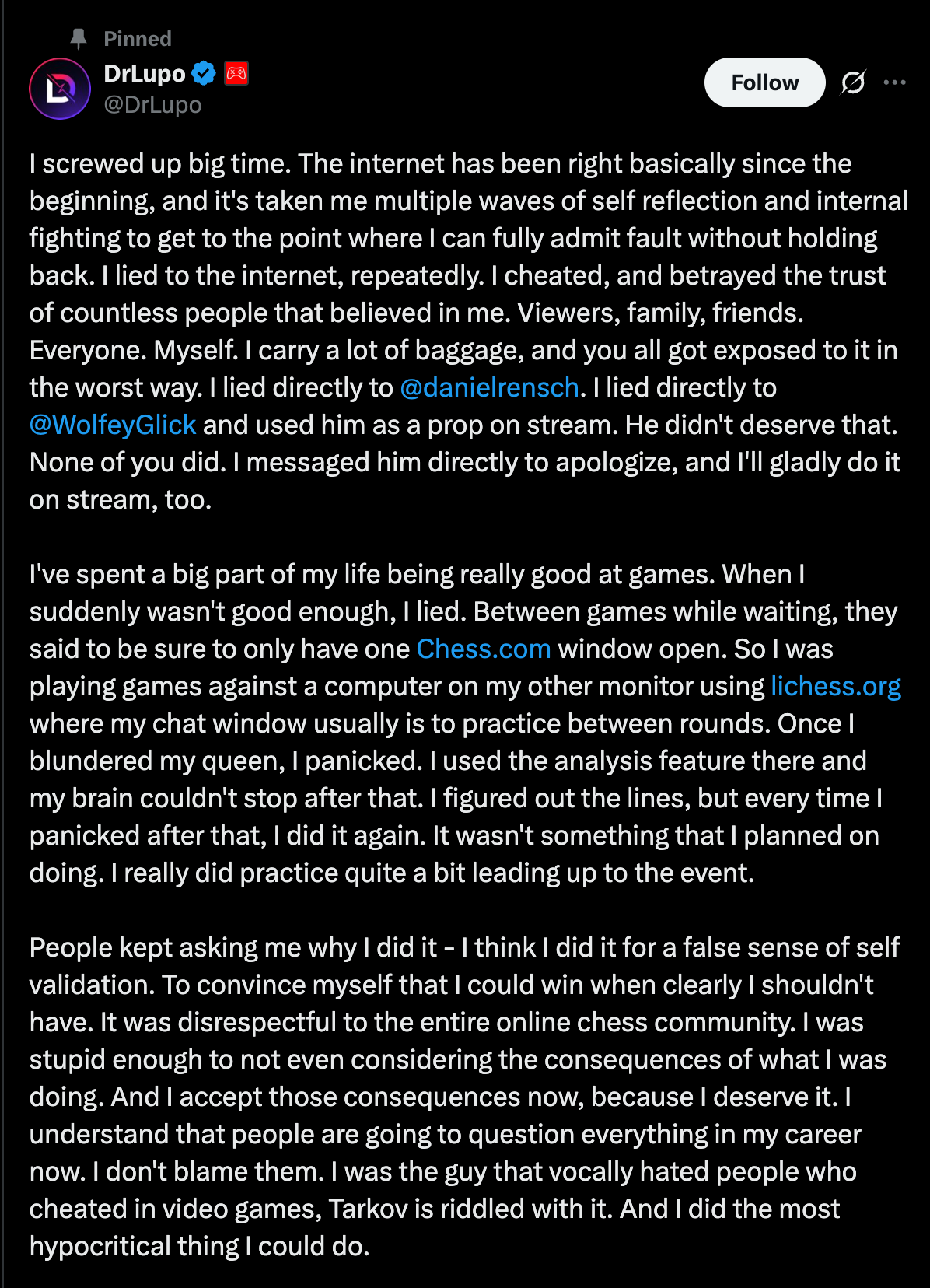

Eventually, he fessed up and made a second larger apology.

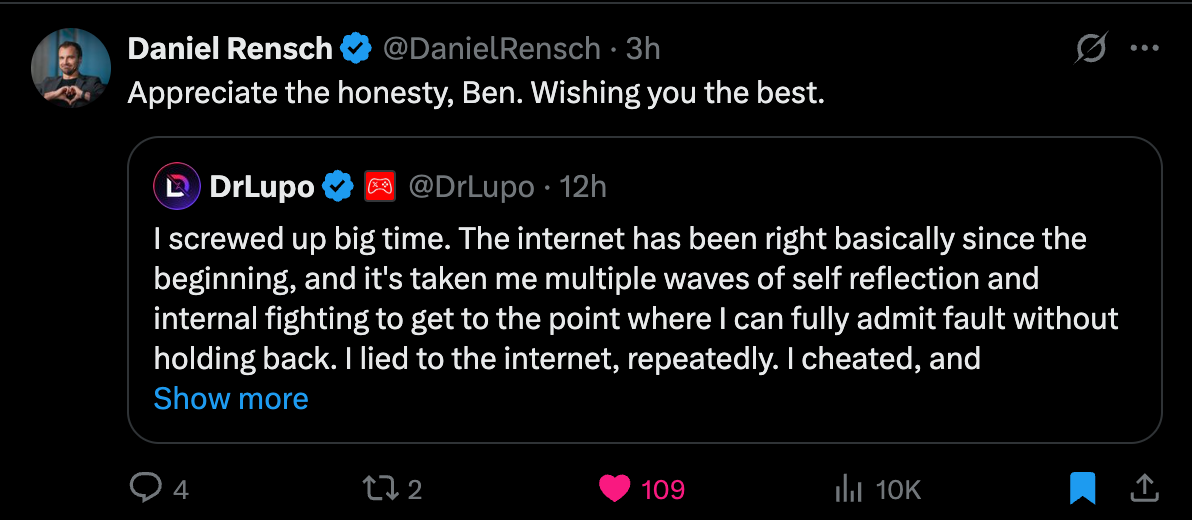

Chess.com’s CEO took it gracefully.

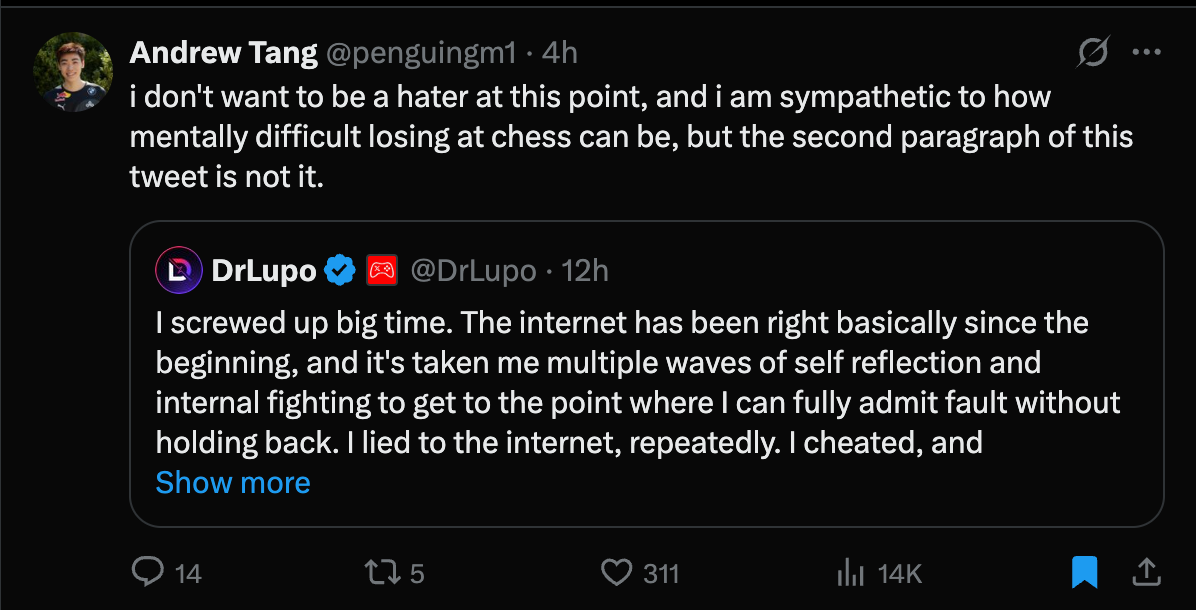

The professional chess player Andrew Tang had the opposite reaction.

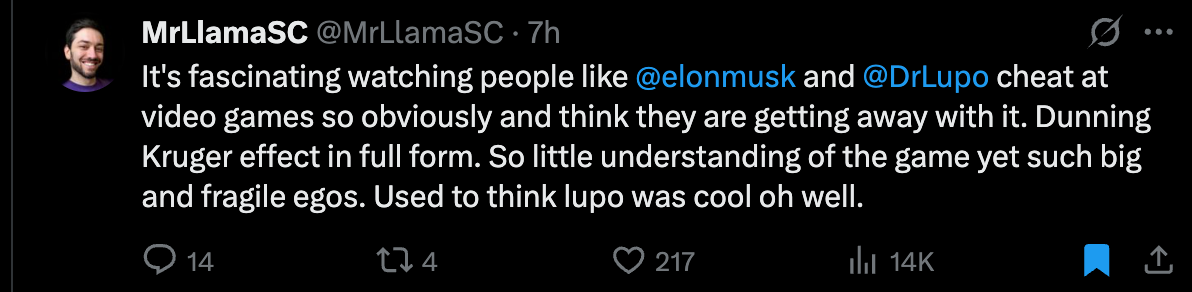

But mostly, viewers and gamers have been harsh and unforgiving.

So much so that you’d think DrLupo had committed murder, as one user pointed out.

My view is that DrLupo’s second apology was honest and about what you would hope for. He names exactly what he did wrong and why, before saying what steps he’s taking to not make the offense again.

And I read the second paragraph differently from Andrew Tang, not as an excuse but as an explanation, and a convincing one at that. He cheated because it was tempting, it was easy, and losing would have hurt his ego. That doesn’t make it right, but it certainly sounds real.

In a novel I’m working on, I have a character like DrLupo who cheats on Twitch for a charity stream. (I want to say, for the record, that this was in my manuscript before any of this happened!) In many ways, the concept of “playing fair” is what the whole book is about. So this episode feels resonant.

But when it comes to literature, really I keep thinking about one of my favorite stories by the late Marina Keegan, The Ingenue. In it, a young couple is playing Yahtzee on an idyllic Cape Cod vacation, when the boyfriend slyly cheats and the narrator can’t understand why.

I was shocked. Literally incapable of comprehending what I’d seen. I felt stabbed, like the air was forced out of my chest, and I looked at him aghast, hurt, shut behind walls. It was unfathomable to me. The game didn’t matter. The stakes were so low. There was no part of me that would—could—ever consider doing what he did. But it was so easy for him. The easiest thing. And that, I realized, had been there all along.

I think this is at the heart of why DrLupo’s apology, as thoughtful as it is, cannot immediately undo the change in perception from his fans and community. When you cheat at something pointless, it reveals how little you valued the people you were playing against, or how much you valued your ego. You have shown a real character flaw.

An apology can’t undo a character flaw by itself—only time and effort can.